Extracts from Glimpses into the formative Years

My mother (aged five) about to fly with Sir Alan Cobham,

the long-distance aviation pioneerMy mother herself, who was a larger-than-life character, was an intrepid traveller. In 1920, when she was only five, her father took her on a flight with Sir Alan Cobham, the long-distance aviation pioneer, in his open-air Tiger Moth bi-plane. In the mid-1930s, a grateful patient of her recently deceased father, William, who was a much-loved doctor, left her a legacy of £1,000. The moment she received it she packed her typewriter, cashed the cheque and said to her horrified mother, ‘I’m off to Europe to write some articles!’ She spent the next six months travelling alone in Italy and Sicily, which was an exceptional thing for any woman to do in those days, far less one of only twenty. In the 1960s, after my sister and I stopped going on family holidays, my mother talked my father into going to the Greek Islands, which were still unknown at the time. Again, he liked the new destination so much he refused to go anywhere else, except back to Spain. But my mother was unusually resolute, so she travelled by herself to Russia, Poland and dozens more Greek islands until she persuaded him to go with her to France, Germany and Italy. . . (page 21)

My mother in Piazza San Marco, Venice,

in the 1930’sWhen I returned from the States, I told my mother I had been to Guatemala. She had worked as a journalist in London prior to the Second World War, and without ado she disappeared and fished out a timeworn article she had written. It was entitled ‘Colourful Guatemala’ and described local festivals where ‘skyrockets shoot up into the starlit sky, and dancing throngs in their best costumes jostle in sixteenth-century churches to light candles and place corn, slices of orange and blossoms at the foot of the altar’. It even described the wind, which had ‘a hothouse smell, warm, damp and scented’.

‘I didn’t know you’d been there!’ I exclaimed.

‘I haven’t!’ she countered without blushing. ‘I just went to the local library, read some travel guides and made it up.’ It was partly from her that I caught my desire to write. After she had a family she stopped writing for publication, but whenever she went abroad she inundated her friends with innumerable postcards crammed with vivid descriptions of tumbledown villages, hunched women in black on donkeys and gnarled men sitting around smoking pipes. If her friends were going to places she had visited, she supplied them with detailed instructions on how to get there, how long it would take, where to stay, where to eat, what to do during the day, what to do at night, and where to go next after they left. . . (page 20)

My Father in Sussex in the 1930’sThe next July my parents took the family for our first summer holiday abroad. Not surprisingly, my sister, Minka, and I were excited as we set off by car to drive from Scotland to the Basque country in northern Spain. On the way we stopped to see my father’s mother, Ethel, an eccentric Communist who lived in a large rambling house in Staines in Middlesex. While everyone was having afternoon tea in the library, I went for a dip in the swimming pool. It obviously hadn’t been used for years, as it was murky and half-covered with water lilies. Unfortunately, my grandmother omitted to tell me it was only a metre deep at the sides. When I plunged off the springboard I didn’t dive out far enough, so I hit my head on the bottom of the pool, and the nearest doctor had to be summoned to put six stitches in my forehead.

The following day we broke the journey in Sussex, where I was born, to see old friends of my parents. Trying to bond with my father, Timothy, I drank two pints of the local potent cider and, within half an hour, vomited over our friends’ carpet. A few days later, we stopped at a hospital in Bordeaux to have the stitches removed. The doctor who attended me was a young trainee, and he was so nervous during the procedure that I had to talk to him non-stop to give him confidence, rather than the other way round. . .

(page 22)

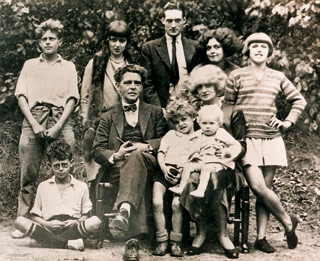

My grandfather, Henry Marriot Richardson, with my grandmother,

Ethel, and their family (my father front row, left) at their large,

six-bedroom house in Dulwich, LondonI must have also inherited an interest in writing from my father’s side of the family. His father, Henry Marriot Richardson, was a playwright and writer, but he was better known as the first salaried general secretary of the National Union of Journalists from 1918 until 1936, and the president of the International Federation of Journalists from 1930 until 1932. As part of his work, he knew H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw and G.K. Chesterton, as well as the press barons Lord Beaverbrook, Lord Northcliffe and Lord Rothermere. My father was also a journalist until, after 1945, the stigma of being a conscientious objector during the Second World War, when he had to work on a farm in Sussex, put paid to his career and he became the publicity director for a large agricultural company instead. . .

(page 21)

The Mather Quintet: my maternal grandmother (left) with her

four sisters c. 1917Now, for the first time in my life, apart from having a few violin lessons at school and writing poems in my teens, I wanted to do something creative. So I decided to become a classical guitarist, despite the fact that, at the age of twenty-three, I had never played the guitar before. In retrospect, I can see that, as well as having loved classical guitar music for some time, I was probably influenced by Eva, my mother’s mother. She was a highly musical woman who, since the age of five, had played with her four sisters, all under the age of ten, in their own quintet. By their early twenties they had become professional musicians and were, as the Mather Quintet, very well known. They even gave a benefit concert in London’s Albert Hall for the families of the victims of the Lusitania, which had been torpedoed, with huge loss of life, by a German submarine in the First World War. . . (page 26)