Open Map

Olemoe Falls, Savai’i IslandSamoa

At first I thought I would be the first person ever to dislike Samoa; rarely have my initial impressions been so wide of the mark.

Imagining it to be the highlight of my first three-month journey through the Pacific, I was disgusted as I wandered along the harbour embankments of Apia, its diminutive capital (population 35,000) on Upolu Island. Samoa had been a New Zealand colony until 1970, but many of the characterful wooden administrative buildings lining the bay were derelict ever since the government had moved across a busy dual carriageway to its new headquarters, a monstrous, Chinese-designed tower block surrounded by acres of tarmac. Elsewhere, luckily, Apia was still lazy and rambling, but I wondered for how long it would remain so.

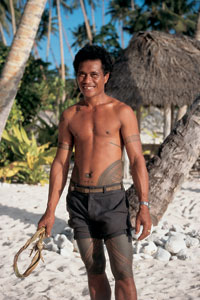

The chief’s son, Oli, showing

his tattoos, Savai’i IslandWeary of wandering the clogged backstreets, I stopped for refreshments in the world renowned Aggie Grey’s Hotel on the waterfront. Founded by one of Apia’s most prominent women, on whom James Michener supposedly based Bloody Mary in his South Pacific Tales, it had been a home for bored US servicemen during World War Two until it became a beacon for Pacific travellers in the late 1940s. Regrettably, the original wooden building had also been recently demolished and now, rebuilt in mock south-Pacific style, it was a fourstar hotel, with its foyer awash with brochures for Western honeymooners, noticeboards for Mobil Oil delegates and expensively dressed Americans discussing the prices of yachts. Nor were its grounds any more appealing, with fake fales (traditional Polynesian thatched huts) named after Marlon Brando and William Holden, who stayed here in the 1950s, and sunbathers reading Jackie Collins by the pool.

That afternoon, I waited outside the covered market for a bus to Vailima, Robert Louis Stevenson’s mansion. The market was full of old Samoan men sharing kava bowls with burly policemen wearing blue lavalavas and white bobby’s helmets. When the bus came, it took me up winding roads to the 300-acre estate high on looming Mount Vaea. Used by the German, New Zealand and Samoan administrations as their official residence after his death, it had been destroyed by cyclones until, financed by wealthy American Mormons, it too had been rebuilt, emerging in 1994 as a lovingly restored, if sanitized, museum. Not that I was given long to see it; an obligatory guide, who was wearing a Royal Stuart skirt – the same tartan Stevenson instructed his servants to wear – rushed me through the dark, mahogany-lined rooms and, apart from fireplaces Stevenson had installed in 1891 to remind him of Scotland, not much was original. . .