Ethiopia

Open Map

Lake Tana

‘What on earth are you going there for?’ my friends asked incredulously.

Woman on Zege Peninsula,

Lake Tana, northern EthiopiaLet’s face it; Ethiopia has an image problem. The name, of course, is synonymous with desert, drought, famine and war. Still, as hostilities with neighbouring Eritrea over a twentykilometre strip of barren border – described as ‘two bald men fighting over a comb’ – were finally over, I set out to see for myself. It was a revelation. True, it is desperately poor, and its primitive infrastructure makes travel exceptionally hard. But, if you can survive, there’s more to Ethiopia than beggars, battered buses and dirt-track roads. How many people know for example that in the fourth century ad this ancient country was among the first to adopt Christianity? How many are aware that the northern half is in fact a peaceful, fertile, 2,500-metre-high plateau the size of France, or have heard of the fascinating ‘Historic Route’ that runs through it?

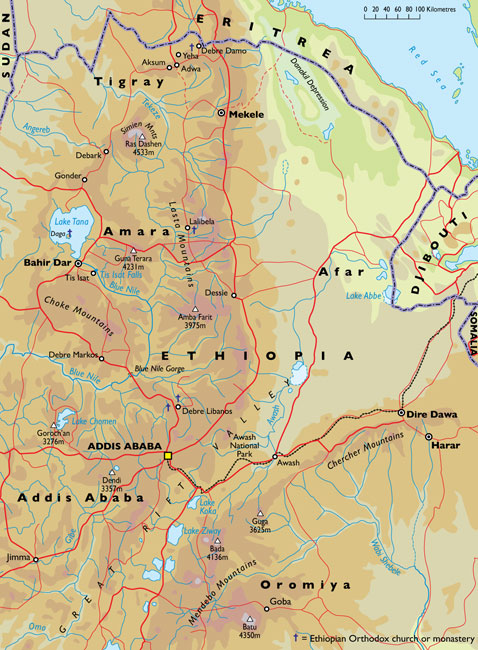

Timkat (Epiphany) Festival in GonderThe trail starts just north of the capital, Addis Ababa, and winds for 800 kilometres north-west through the plateau to Lake Tana, the Blue Nile’s source and site of island monasteries containing unique Ethiopian Orthodox Church frescoes, until it disappears north. The long, three-day overland journey along the route wasn’t easy. Every morning at five o’clock, white-garbed crowds, phantom-like in the moonlight, thronged padlocked gates before pouring into compounds and onto the antediluvian buses. The frantic battle to board the day’s only public transport along the route was just the beginning of the ordeal. The bus, its overheated engine screaming, ground along the dusty, rutted roads, hour after bone-shaking hour. In wayside villages, open-mouthed crowds would goggle at faranji (foreigners), and countless ragged children along the roadside continually shouted ‘you, you!’ If anything, nights in dingy, fly-blown hotels were even worse, with the panting of men and women behind paper-thin walls making sleep impossible.

View of the Simien Mountains from the escarpmentNevertheless, it was intensely rewarding. Each day revealed biblical scenes. Streams of donkeys and barefoot, scrawny-legged peasants trudged along the roadside. The men wore smudged, ragged gabis (long white robes) and had wooden staves slung across their shoulders or immense bundles of wood on their heads. The women carried black umbrellas, and clay water-pots on their backs. Everywhere motionless children stood in dry, yellow fields, tending herds of humpbacked Zebu cattle or sheltering from blistering midday heat under clumps of shady eucalyptus. Thatched villages dotted the gently rolling hills. Occasionally, distant figures on horseback trotted across the brown plains, which were broken only by horizontal, spreading acacia. Aboard the bus, behind the driver, a sea of faces wrapped in headscarves nodded rhythmically to cassettes of religious songs as we rattled ever westwards into the blood-red sunset.

Woman in western Ethiopia

The highlights of the trail were unforgettable. A hundred kilometres north of Addis a side road branched off to Debre Libanos, Ethiopia’s most holy monastery. Deserted, apart from families of playful gelada baboons, the road ran along the rim of a gigantic escarpment and wound down through trees to a village. In the main street, which was lined with stalls, pilgrims pored over religious bric-a-brac and bibles in Amharic, Ethiopia’s lingua franca. . .